By:Abdullahi Inuwa

Recent United States visa restrictions and large-scale deportations affecting Nigerians have reignited a difficult national conversation: how years of alarmist narratives, misinformation and exaggerated claims about insecurity in Nigeria helped shape punitive international responses against the country.

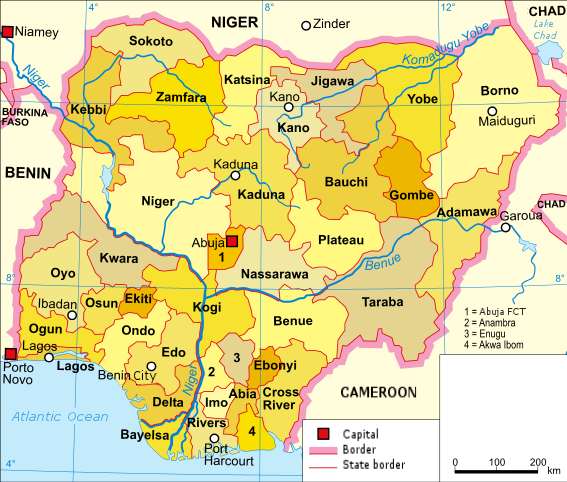

Nigeria undeniably faces serious security threats. Terrorist violence by Boko Haram and ISWAP, armed banditry, farmer–herder clashes, transnational jihadist movements, climate stress and porous borders have created a complex and dangerous landscape. These challenges are real, deadly and demand sustained solutions. But the growing tendency to reframe this violence as a coordinated, state-sponsored “Christian genocide” has increasingly come under scrutiny — not only within Nigeria, but also among independent international observers.

For years, a loud and coordinated advocacy campaign — driven largely by some Nigerian activists, politicians and diaspora-based pressure groups — presented Nigeria as the global epicentre of religious extermination. The narrative was emotionally charged, but often rested on figures and claims that were exaggerated, unverifiable or demonstrably false.

What began as domestic grievance politics soon morphed into international propaganda. Between 2021 and 2024, lobby groups accused the Nigerian state of deliberately aiding or shielding jihadists allegedly carrying out daily mass killings of Christians. Some claims suggested that as many as 1,500 Christians were being murdered every single day — a figure that would amount to over half a million deaths annually, rivaling or exceeding casualty levels in the world’s most intense war zones.

Another widely circulated claim alleged that between 2010 and October 2025, about 185,000 Nigerians were killed purely for religious reasons — including 125,000 Christians and 60,000 Muslims — alongside assertions that more than 19,000 churches were destroyed and over 1,100 Christian communities completely seized by jihadists, supposedly with government backing. These figures were frequently attributed to activist NGOs created specifically to advance such claims.

Yet repeated attempts to independently verify these statistics failed. No credible conflict-monitoring body — including ACLED, UN agencies, major international human rights organisations, or Nigerian institutions such as the Police, DSS and the National Human Rights Commission — corroborated these numbers. In a country of roughly 240 million people, casualty figures of such magnitude would have triggered a full-scale global humanitarian emergency comparable to Syria, Ukraine or Gaza. That never happened.

Security analysts, including Zagazola Makama, have consistently noted that while religiously motivated attacks do occur, Nigeria’s violence is not a single-faith war. It is a multi-layered crisis driven by criminal economies, insurgency, arms proliferation, environmental pressure, weak governance and cross-border militancy — affecting Muslims, Christians, traditional worshippers and entire communities alike.

Despite the absence of empirical backing, the genocide narrative was repeatedly weaponised to internationalise pressure against Nigeria. It gained traction within parts of U.S. political circles, evangelical advocacy groups and segments of Western media. Some Nigerian politicians went as far as lobbying foreign governments for sanctions, arms embargoes and even external intervention against their own country.

The expectation among agitators was that a Trump-led administration would impose harsh sanctions or deploy military force. What followed, however, was a very different — and more far-reaching — outcome. Rather than direct intervention, Washington recalibrated its approach: offering technical security cooperation to Nigeria’s armed forces, while tightening border controls, immigration enforcement and visa policies at home.

Nigeria was subsequently placed under partial U.S. travel restrictions. American authorities explicitly cited terrorism concerns linked to Boko Haram and ISWAP, weaknesses in traveller screening, document integrity challenges and broader vetting difficulties. The result was tougher scrutiny of Nigerian nationals, visa suspensions across several categories, and a reputational downgrade that spilled into trade, education and diplomacy.

Ironically, portraying Nigeria’s insecurity as an all-out religious war produced the opposite of its stated goal. Rather than safeguarding Christian communities, the narrative provided propaganda fuel for extremist groups.

Terrorist organisations such as ISWAP, JAS and al-Qaeda-linked JNIM elements — now probing parts of North-Central Nigeria — exploited global portrayals of Nigeria as a battlefield of faith. By attacking churches, clergy and Christian settlements, these groups sought to validate international narratives, provoke retaliation and ignite broader sectarian conflict. This tactic mirrors jihadist playbooks across the Sahel: polarise society, delegitimise the state and attract recruits through manufactured religious war.

Intelligence from states like Kwara and Niger indicates that JNIM-linked cells have actively exploited communal fault lines along the Benin–Nigeria corridor, recruiting vulnerable youths with language crafted to echo international persecution narratives.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security has justified its hardened stance using data-driven metrics: visa overstay rates, terrorism risk assessments, weak civil documentation systems and law-enforcement information gaps. Since January 2025, the department has recorded over 2.5 million deportations and self-removals — a policy shift that disproportionately affects nationals of countries labelled high-risk, Nigeria included.

Crucially, those paying the price are not terrorists hiding in forests. They are Nigerian students, professionals, traders, pastors and families. The bandit has no interest in a U.S. visa; the ordinary citizen does.

Notably, as visa restrictions and deportations took effect, the once-deafening genocide rhetoric faded. Many of the loudest advocates went quiet, perhaps confronted by the reality that the consequences landed on Nigeria as a whole, not on imagined perpetrators. It underscored a hard truth in global politics: when a country’s internal crises are exaggerated into existential falsehoods, foreign governments respond not with rescue, but with containment.

Nigeria’s security challenges are serious and demand reform, accountability, diplomacy and international cooperation. But turning them into religious absolutes, inflating casualty figures and lobbying for foreign punishment undermines national security rather than strengthening it. Worse still, it feeds extremist propaganda, deepens communal mistrust and invites policy decisions based on distorted perceptions.

When internal problems are projected globally without balance or factual discipline, the response is rarely sympathy. It is restriction, sanction and isolation. In the long run, propaganda — even when packaged as advocacy — erodes diplomatic goodwill and damages the very citizens it claims to defend.

False alarms fracture social trust, embolden violent actors and inflame the fault lines terrorists are eager to exploit. Emotion may mobilise attention, but facts shape policy. And in the end, exaggeration weakens resilience, leaving societies more exposed to the threats they seek to overcome.

Source:@ZagazolaMakama